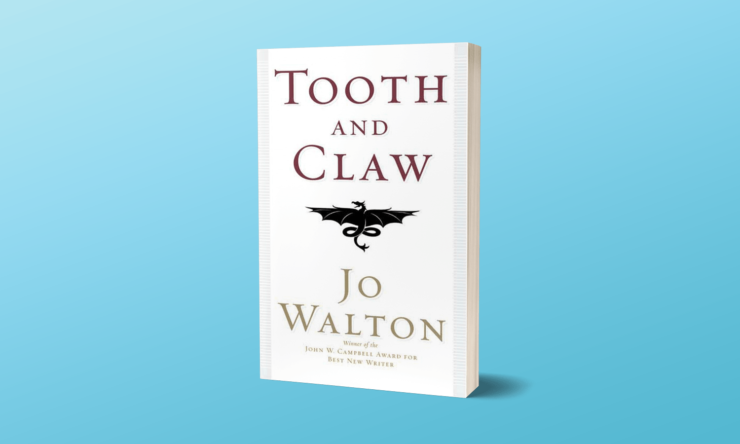

I’m delighted that Tooth and Claw is being given away this week—I hope people will enjoy reading it in these difficult times. The title comes from Tennyson talking about how much humans suck in In Memoriam: “Tho’ nature, red in tooth and claw, with ravine shrieked against his creed… no more? A monster, then, a dream, a discord. Dragons of the prime that tear each other in their slime were mellow music matched with him.” And that’s the book, really; the easiest way to sum it up.

I’ve recently read Tooth and Claw aloud to an audience of friends and fans on the Scintillation Discord server, so it’s much fresher in my mind than a book I wrote in 2002 would otherwise be. It’s a fun book. It has deathbed confessions, marriage proposals, hats, buried treasure, and all the other paraphernalia of a Victorian sentimental novel. It’s funny in places, horrifying in places, and sentimental in places. And it’s all about dragons who eat each other. Every character is a dragon. They wear hats, and live in civilized, decorated, caves and cities, but they eat raw meat (when they can’t get dead dragon), they wipe the blood off their scales after meals, and the female dragons have to be protected because they have no flame and hands instead of claws so they can’t defend themselves.

It says on the hardcover jacket copy “You have never read a book like Tooth and Claw” which is absolutely untrue, because if you have read Anthony Trollope’s Framley Parsonage you have read a book very much like Tooth and Claw except that Trollope was under the mistaken impression that he was writing about human beings. I had the idea for Tooth and Claw when I was simultaneously reading both Trollope and a fantasy book about dragons, and my husband asked me a question about the former and I answered about the latter, and I suddenly realized in a flash that Trollope made much more sense if the characters were dragons.

So I took this one idea, that Victorians are monsters, but monsters are people, and if you translated Trollope’s dragons into a world where they make sense as people, dragon-people, then that would reflect back interestingly in both directions. Then I set to thinking it through, in all its implications and second order implications. I worked out the last six thousand years of dragon history, since the Conquest—I needed that long because they live four or even five hundred years, if they don’t get eaten first, so that was only fifteen lifetimes. I worked out their biology, and that dragons need to eat dragonflesh to grow larger, and the way social pressures affect their biology. I did this all backwards, because I was starting with Trollope and translating, so I was essentially retconning the worldbuilding to get it to where I wanted it.

Trollope seemed to sincerely believe that not only is it utterly impossible for anyone female to earn her own living (despite his mother having supported their family) but also that women can only love once, that they exist in an unawakened state but when they fall in love they imprint, like baby ducklings, and can never love again in any circumstances. I made this bizarre belief into a physical biological thing for my dragons—maiden dragons have golden scales, and when an unrelated male dragon comes too close, bang, their scales turn pink, it’s utterly visible to everyone and you can’t get back from that. If this isn’t a formal engagement then the maiden is quite literally ruined, and everyone can see. It makes things very awkward, and I do a lot with this scale-change in my story.

Then there were all the questions of how and what civilized dragons eat, and the problems of providing fresh meat supplies in the city, and the economics of having female dragons being employed as clerks because it’s much easier to write with hands than claws, and the millinery, and their religion—the two variants of the religion, and the Conquest and all the other history that had brought them to that point. And then the issue of parsons ceremonially binding their wings and then the servants having their wings bound against their consent, and the whole feudal issue of lords eating the weakling children in their demesne and… it all ramified from there.

And as I did this worldbuilding, I realised I could just take Framley Parsonage, one of Trollope’s Barchester novels, and just translate it into the dragon world—I could just steal the plot and it would be all right, it was out of copyright, nobody would care, and that would be fun.

So I looked at the plot of Framley Parsonage and most of it translated beautifully into my dragon world. But weirdly, there were a few things that didn’t work, or that I had to reshape or expand. Some of the reshaping was so I could give a wider view of the dragon world. FP is about a brother and sister, Mark and Lucy. (In T&C they are Penn and Selendra.) In FP they have another brother and two sisters who are barely mentioned, but in T&C I needed to develop the lives of the other siblings almost as much, so that I could show the world and the options, because I wasn’t just talking about dragons and I wasn’t just talking about Trollope, I was talking about how Victorians were monsters. Avan, the brother, I mostly took from another Trollope novel called Three Clerks. And there are plenty of characters in Victorian fiction like Berend. But Haner, whose Trollope equivalent barely has two lines in FP, became a significant character for me because I wanted a way to talk about two very important and very bound-together nineteenth-century issues, slavery and female emancipation, even though Trollope wasn’t particularly interested in either of them.

Buy the Book

Or What You Will

My favourite thing I took from Trollope was a Trollope-style omniscient narrator who in Tooth and Claw is implicitly a dragon writing for other dragons. So I had a lot of fun with the space of expectations there—when the narrator is expecting the dragon audience to be shocked, shocked, at cooked meat, but expecting complete audience sympathy with the idea of eating the corpse of your dead father, while of course I am aware that the real reader’s sympathies are going to be in different places.

I had one other issue with reader sympathy which caused me to make the other major change in the original plot. In FP, Mark co-signs a bill for a friend, putting himself into debt and difficulties which he struggles with throughout the novel. I had to change this plot thread utterly, because doing something like that is so entirely unsympathetic to a modern reader. When I read it, I felt like Mark was just an idiot, and it was difficult for me to care about him—even though I’d read a zillion Victorian novels and knew this was one of the standard conventions. And so I knew I had to change that, and have something that the modern readers would sympathise with, as Trollope’s original Victorian readers sympathised with Mark but we can not. Literary conventions change from age to age and genre to genre, and that one just doesn’t work any more. So I changed it.

And at that point, with that changed, and with the new material about Haner, and with the fact that everyone is a dragon, the story really had changed quite a bit and perhaps it wasn’t as close to Framley Parsonage as I thought it was. Nevertheless, if you want a sentimental Victorian novel about dragons who eat each other, here it is.

Tooth and Claw is available to download for free until midnight (Eastern Time) on May 23rd, 2020.

Jo Walton is a science fiction and fantasy writer. She’s published two collections of Tor.com pieces, three poetry collections, a short story collection and thirteen novels, including the Hugo- and Nebula-winning Among Others. Her fourteenth novel, Lent, was published by Tor in May 2019. She reads a lot, and blogs about it here irregularly. She comes from Wales but lives in Montreal. She plans to live to be 99 and write a book every year.

This book astounded me when I first read it, and I’m highly looking forward to re-reading it, so thanks greatly both to you and to Tor.

This is the book that sparked my continuing interest in Jo Walton’s prose. (Long-time fan of her poetry.) Totally marvelous!

This was my gateway Jo Walton book. I’ve now read it several times and found more in it on each tour, though I think Among Others is my current favorite. Looking forward to the new book, too!

Of course you could have had one of the main characters do something ridiculously stupid; you would have had to classify the book as a Young Adult novel though, as the basic premise for that genre is that the hero/heroine does stupid things to put themselves in jeopardy…

I’ve always heard of Tooth and Claw but never read it; I downloaded the e-book but I will say that it was this reflection that propelled it to the top of my to-read list. Excited to read the scaly version of Framley Parsonage!

Love it!

I had read Framley Parsonage quite recently when Tooth and Claw came out. (I have read a lot of Trollope.) This is no doubt why I giggled madly throughout.

Thank you!

I have to confess, I have never read a single Trollope novel – not one. Mostly because he interests me even rather less than Dickens, and I don’t like Dickens very much. At least Dickens writes about people I’m interested in, even if I detest his language.

But I did enjoy Tooth and Claw, fhough when reading it I thought it was rather like “if Jane Austen was a dragon”.

Thank you very much!

I loved T&C, second only to the great Among Others among the Jo novels I’ve read.

This book was an absolute delight! I laughed out loud several times, and I never resented a viewpoint change because all of the characters were so interesting. The fact that they were dragons made the predictability of a Victorian plot so much more engaging (the threat of being eaten made all the conflict feel very high stakes!). Thank you for a great giveaway, Tor, and I will definitely be picking up more Jo Walton books.

I’m a fan of Trollope’s works already, so I really enjoyed the references. Thanks, For, for introducing me to Jo Walton and this delightful book.

exactly 2 months later, I finished this book…I loved it! I want a sequel! Have you thought about writing one, Jo? I certainly noticed a few situational threads that could be followed, even if it didn’t seem to end on a cliff-hanger for the characters. Meanwhile, thanks for this one, Jo and TOR.